Dates

Jan 15 – Feb 28, 2026

Today

10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

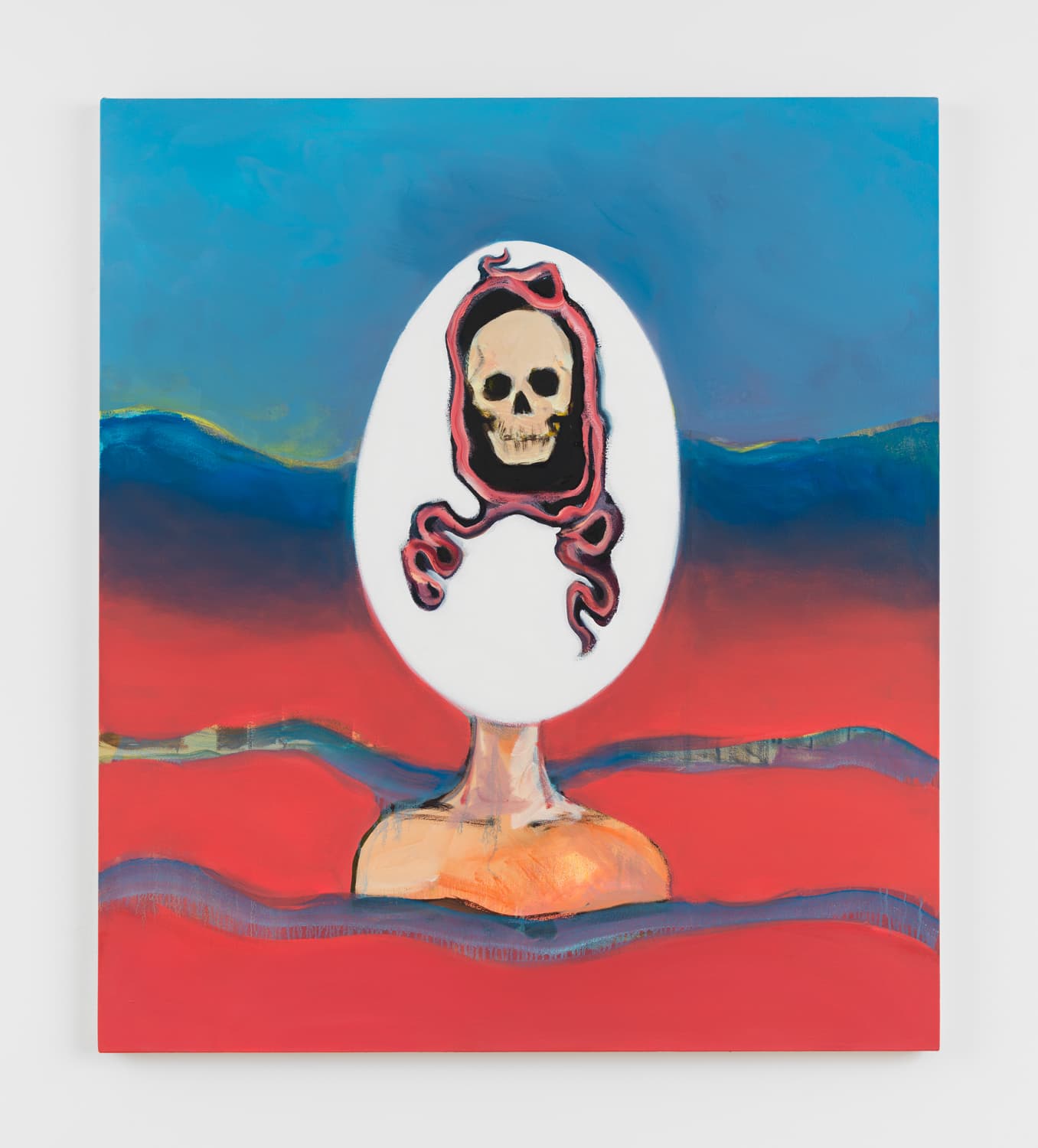

<p>Magenta Plains is pleased to present Antechamber, a solo exhibition of new paintings by Becky Kolsrud. This will mark her first with the gallery. Kolsrud’s painting practice encompasses a lexicon of allegorical imagery relating to cycles of life and death, spiritual conceptions of femininity, and a contemporary engagement with the surreal. Eggs, skulls, fish, and mirrored images recur across the work, as iconographic touchpoints for the complex intellectual lineage which Kolsrud is engaging. </p><p></p><p>Antechamber showcases Kolsrud’s focus on an allegorical library of imagery, which she utilizes to demonstrate how the concepts first explicated by the Surrealists can be applied to a contemporary investigation of identity, and how that identity is broken down and reconstituted through painting. Kolsrud suggests associations between these grand themes and the embodied feminine experience– as a universal exploration of the dualities which shape our day-to-day lives. </p><p>In Antechamber, Kolsrud’s surreal imagery investigates the duality of life and death, the sacred and profane. One salient motif in the exhibition is a skull, wreathed in intestines, superimposed over an egg. In the painting Eternal Return, Kolsrud uses this image as a sculptural portrait bust, sitting in front of an abstracted landscape. A symbol of death, the skull is encased in a symbol of birth, the egg, presented to the viewer as a single object–the cycle is enclosed within this one image. In Marriage, Kolsrud utilizes the skull for different purposes: here it sits inverted atop the head of a nude female figure, emerging from a primordial, abstracted pool, wrapped in her hair. Emerging from the very top of her hair is a red apple, a symbol of knowledge and also life–the figure’s hair is now the vessel for this surreal cycle. Kolsrud triangulates her iconography to explicate a narrative through relation– differing images serve related but distinct purposes in each composition.</p><p>Central as well to Kolsrud’s exhibition is imagery drawn from George Bataille’s surrealist journal Acéphale, which published only five issues from 1936 to 1939 but had an outsized influence on the early surrealist movement, which centered sex, op violence, and death in opposition to reason as a primary principle. In Kolsrud’s painting Acéphale (After Masson), she appropriates the cover image from Bataille’s journal, originally authored by Andre Masson, for her own purposes: a headless figure, modeled after Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, holds a dagger in her left hand and a flaming heart in her right. Her entrails are exposed to the air, and a skull sits at her groin. The key distinction between Kolsrud’s image and Masson’s is that Kolsrud’s is female, floating in front of a ghostly image of a wrought-iron gate, which has been shaped into the form of wings floating behind the figure. While Masson’s figure is a rebuke to Leonardo’s humanist portrait of man as both the object and arbiter of Reason, Kolsrud’s figure both pays tribute to the surrealist legacy of Acéphale while suggesting a transition to something beyond the dichotomy it proposes. Kolsrud relates the aesthetic philosophy of Bataille’s Acéphale to the feminine form, complicating Bataille’s narrative by alluding to an alliance between femininity and the viscerality of historical surrealism, one which exists beyond the binaries of modernist thought.</p>